We Love How Black Panther

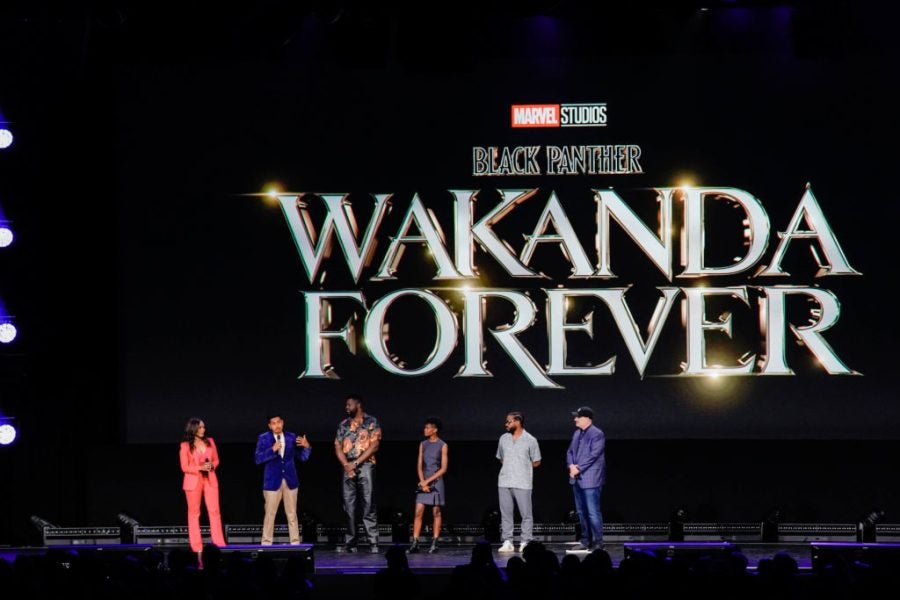

The Walt Disney Company via Getty Images

Angela Bassett, Tenoch Huerta, Winston Duke, Letitia Wright, Ryan Coogler

We Love How Black Panther Marvel’s blockbuster “Black Panther 2: Wakanda Without end” immerses us over again within the fictional African Kingdom of Wakanda, a Black refuge from the predatory nation states of Europe and america. The Black Panther, generally known as T’Challa, was the previous king of this wealthy and hyper-modern asylum from the colonialists and capitalists who impoverished the true continent of Africa, but he perished in the primary “Black Panther”released in 2018.

[Editor’s note: SPOILER ALERT, but if you haven’t seen the film yet, what are you waiting for?]

The sequel incorporates a stunning revival of his legacy after we learn that the Black Panther left behind a son along with his wife Nakia, a Wakandan warrior. In a mid-credit scene meant to establish the following “Black Panther,” Nakia and her son are revealed to have been living in Cap-Haïtien, a northern port city that was famously the capital of the nineteenth-century Kingdom of Haiti, ruled by King Henry Christophe.

It will not be only the story of the first and last king of Haiti that the film evokes with this setting. The life and legacy of Christophe’s comrade-in-arms, the famous revolutionary hero Toussaint Louverture who helped end slavery on the French-claimed island of Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti), surges forth when T’Challa’s son tells his father’s sister, Shuri, who has recently arrived in Cap, that his “Haitian name” is Toussaint. “Toussaint is a stupendous name,” she softly replies.

Because the inheritor of his father’s throne, the brand new Toussaint will due to this fact be the one to hold into Wakanda the heritage of Black freedom and equality instantiated by Haiti in 1804 when it threw off the yoke of its very real colonizer, France, and have become the primary modern nation to permanently outlaw slavery.

Starting in 1791 Toussaint Louverture, who had been enslaved until the 1770s, led quite a few slave revolts on Saint-Domingue. By 1794 he had helped force the French to officially emancipate all of the people they were enslaving there and in other French colonies. After reconciling with France, Louverture became the second Black man after Thomas-Alexandre Dumas (the famous novelist’s father, also born in Saint-Domingue) to attain the rank of general within the French military.

Louverture had also successfully led France to defeat the invading armies of Spain and Great Britain. His military, social, and political aptitude, joined along with his ardent determination, are captured by one in every of his many famous remarks: “I’ve been fighting for a very long time, and if I have to proceed, I can. I actually have needed to take care of three nations and I defeated all three.”

Louverture’s power only grew as he achieved the title of governor-general and issued his own structure for the colony. Meanwhile French leader First Consul Napoléon Bonaparte plotted to reinstate slavery while making it his mission to subdue the Black man whom he considered to be his best rival. Just like the colonizers in “Black Panther,” who played a task in T’Challa’s downfall, Bonaparte defeated Louverture with betrayal and deception.

In June 1802 Louverture was tricked by a white French general into a gathering where he was arrested and placed aboard a ship that was setting sail for France. He was subsequently left by French jailers to die in a jail within the Jura Mountains, never to see his wife and youngsters or his homeland again.

Not long after Louverture’s arrest and deportation, his best fear got here true. France issued a decree that reinstated slavery in its overseas colonies. But Louverture had already prophesied France’s ultimate inability to re-enslave Saint-Domingue when he uttered this iconic phrase, “In overthrowing me, you’ve done not more than cut down the trunk of the tree of liberty – it’s going to spring back from the roots, for they’re quite a few and deep.”

Just as various leaders and soldiers from different parts of Wakanda are vital to its defense and success, Haitian independence was in the long run achieved by a various array of formerly enslaved individuals from not only Saint-Domingue, but West Africa and other islands within the Caribbean.

With its beautiful tribute to the Haitian Revolution, and the Haitian people of today, “Wakanda Without end”joins a protracted tradition of storytellers who evoked the spirit of Louverture to discuss global Black freedom struggles. Quite a few writers, artists, and activists, including the British poet, William Wordsworth, the French poet and playwright Alphonse de Lamartine, the US American abolitionists William Wells Brown, Wendell Phillips, James McCune Smith, David Walker, and Lydia Maria Child, attached Louverture’s name to the fight for abolition within the Americas. Indeed, within the nineteenth century Louverture was, after the novelist Alexandre Dumas, probably the most famous Black man on the earth. Louverture continued to be celebrated by writers from the Black mental tradition within the twentieth-century, too, like C.L.R James, Langston Hughes, Aimé Césaire, and Édouard Glissant. Louverture even makes a cameo appearance in Ntozake Shange’s 1975 choreopoem For Coloured Girls Who Have Considered Suicide.

The empowered Black future that the “Black Panther” franchise continues to ask us to lovingly look towards with Wakanda, and now Haiti, is a reminder that we might be inspired by how Toussaint Louverture lived as we always remember how he died. “I used to be born in slavery,” Louverture once wrote, “but received from nature the soul of a free man.” Although Louverture was killed in French captivity several months before Haitian independence was declared on January 1, 1804, the hope for enduring Black freedom carried into the world by the revolutionaries of Haiti, and that the very name Toussaint has called forth for 2 centuries, won’t ever die, unless we let it.

Marlene L. Daut is Professor of French and African American Studies at Yale University. She is the writer of Tropics of Haiti: Race and the Literary History of the Haitian Revolution and the forthcoming Awakening the Ashes: An Mental History of the Haitian Revolution.

No Comments

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.