Toward the tip of my teens, it began to dawn on me that my face was probably fully formed. That no radical change was forthcoming. That even back once I still held out hope, my features were meanwhile settling, treacherous, right into a mediocrity which surprised, humiliated, crushed me. In other words, I used to be not going to be any great beauty. I used to be only going to be what I used to be: attractive occasionally, like most individuals, relative to whoever happened to face nearby. I used to be horrified; I couldn’t recover from it. Being average-looking is, by definition, completely normal. Why hadn’t anyone prepared me for it?

I couldn’t have discovered I used to be plain without discovering K was pretty. She is my friend of a few years. Back then, it obsesses me: how we make one another exist. We attend elementary school together, then highschool. She enrolls at a close-by college. Her tall grants me my short; my plump her skinny; her leonine features my pedestrian ones. I resent her as much as I exult in her company. In between us, and without words for it, the feminine universe dilates, a continuum whose comparative alchemy seems designed to confront me, make me suffer, lift her up. Her protagonism diminishes me, or does it? I confuse myself for a very long time considering I’m the planet, and K is the sun. It takes me an extended time to forgive her.

Comparison steals my joy, however it also gives me a narrative. All in all, it feels radical to make a world together, she and I, a silent tournament of first kisses, compliments, report cards. I live at a set point from K, her lucky arms, her lucky neck, her lucky elbows. I pursue beautiful friends like some women do men who will strike them in bed at night. On account of our addictive relativity. On account of my envy, which I’ve made, like many ladies, the key passion of my life.

●

There’s something gorgeously petty about many ladies’s lives. They’re not attempting to be great. They’re attempting to be higher. It’s why women food regimen together; dye their hair light, then dark, then light again; dress for one another; race to get engaged; wait to get divorced; discover a taken man more attractive than a free one. Develop into girlbosses in droves after which give it up. A lady can spend her whole life in real or imagined competition along with her friends, finding herself within the gaps between them. Especially in the sport of looks, there isn’t any excellence that just isn’t one other woman’s inadequacy, no abundance that doesn’t mean lack. An excellent beauty is discovered, like crude oil, or gold. Which means in a parched desert, or a unclean riverbed, where the remainder of us must languish. Our democratic sensibility commands us to raze all unfairness. Yet the best way we sacralize beauty, our treatment of the ladies who attempt to level it, our satisfaction when nobody can, calls our bluff.

For me, the humiliations stack up. I nurse them like little children. I pick at them like scabs. The horrid boy I desperately love, who pretends to like me, studying K’s legs on the trampoline. We’re seventeen, and I study them too. Up and down, slender, hairless, vanishing up the thighs, into the sun. Later he sends her a message on Facebook. She does nothing to betray me. What I need is for those legs and the mat of the trampoline to go rigid, to snap, for her bones to spray and splinter, to pierce me through the eyes, so I cannot take a look at either of us anymore.

Or, a pair years later, when I feel I’ve matured, gotten over it, displaying my fake ID at a university party. It’s my friend’s, I explain. It’s K’s. How funny. It really works, we glance barely enough alike. A drunken classmate laughs. “Yes,” he says. “Except she’s hotter than you.” My face silences him, then the room. His words spread my legs, pass a hand through me, find something dying. He apologizes until I console him. I return to my dorm and drown in abjection, almost pleasurably at this point. I’d wish to call my mother, whom I resemble. Except that in all of our talks of puberty, she omitted this. She gave me my face and felt guilty; I needed to learn for myself how my suffering held something up.

My very own inglorious adolescence ends with me dumped, over brunch, at twenty. He has a robust jaw which dazes and a soft birthmark, near the mouth. He’s ten years older than me. That last bit just isn’t the part that hurts. It’s that he’s telling me about one other girl. “She’s amazing,” he says. “I haven’t felt like this in an extended time.” I feel of what we’ve done for a very long time and I am going to the toilet and vomit. After I come back he’s still speaking. I ponder, in silence, what it will be wish to be the kind of girl about whom they are saying, he can’t shut up about her. “She’s a author,” he tells me, with love in his eyes. He looks so handsome, I need to kiss him, exactly now, when, because, he can’t shut up about her. I am going home, look her up, write a poem, recover from him as soon as I get it published, considering vaguely, see, there, that was easy, take that—I could be less lovely, but there are other competitions, I is usually a author too.

●

In those bad years I read and reread a story by Émile Zola called “Rentafoil.” A satire, it tells of a wicked entrepreneur, Durandeau, who cooks up a nasty scheme of renting out ugly women as living foils for better-looking ones. Strolling around nineteenth-century Paris, observing “two girls tripping along,” one pretty and one ugly, Durandeau realizes that the ugly woman is an “adornment worn” by her prettier companion. She makes her look good. Her asymmetry sets off her symmetry; her dull face, her shining one. For five francs an hour, Durandeau’s agency makes available to the “upper crust” ugly women to pull about town. There’s nothing just like the “pleasure of a reasonably woman leaning on the arm of an unsightly one,” knowing herself enhanced. And nothing just like the sorrow of their Foils, who “fret and fume and sob” at night. Finally, the narrator confesses that he “may write the Secret Memoirs of a Foil,” inspired by one “terribly jealous” worker, lovesick and bitter, who reads an excessive amount of. “Are you able to imagine her resentment?” the narrator asks. I could.

But take the primary plain girl that inspires Durandeau. She isn’t employed or receiving a salary, but she should be getting something. Or else why on earth would she tolerate it? The unfairness of beauty, the pinch of being its friend. The comforting fable says: the nice beauty hurts us like a splinter but helps us like a measuring follow understand ourselves. Affords us insight, depth. A chance to compensate. In spite of everything, it’s the plain woman about whom the narrator of “Rentafoil” wants to put in writing, not the gorgeous one. I study that poem by Yeats. Waxing about “Two girls in silk kimonos, each / Beautiful, one a gazelle.” How casual, I feel. How vicious. If she read that, the girl who wasn’t a gazelle, she probably never recovered. It strikes me only later that she won’t have desired to. For what we tolerate of beauty—that pinch—can be, curiously, what we reap from it.

From Austen to Ferrante, women’s literature is ripe with dyads of girls, made up of a lovely half and a less beautiful half. Here, the arbitrariness of beauty plays out in long, anguished plots, games of chutes and ladders, whereby some women find themselves socially, magically, economically mobile, and others don’t, no less than not so easily. We recognize the “winner” as soon as we read what she looks like. In first-person stories, as a rule, it’s not the narrator. These plain heroines yearn for, resent, are fascinated by, love, hate, cannot avoid, their more beautiful, fortunate counterparts. They articulate a precisely feminine pain I do know well, worse than menstrual cramps. A way of 1’s own plainness. Inferiority. An envy so profound and wistful it is nearly sexually charged.

This tone in women’s literature, this snake twist of the belly that signals envy in the identical place as desire, engrosses me. A number of the most exquisite passages of eroticism are within the voice of girls envious of other women. Wanting them? Sometimes. Wanting to be them? Naturally. I watch K do the dishes, in her bikini top and her peasant skirt, and the tight abdomen that’s an insult, and the overhead light that haloes her hair, careless, the soap, the suds, the satisfaction she must feel. In that moment, I need to take the dishcloth and wipe my face from the face of the earth.

●

I read, at first, in quest of consolation prizes.

Within the Neapolitan quartet, Elena Ferrante shows how unfairness, like money, accumulates; beauty forms the mask of what crushes, monopolizes, outshines. Lenù, the narrator, is a dogged teacher’s pet, born into poverty, who becomes a successful feminist author mainly because of her diligence. Lila, her best friend, is a wünderkind. Together with “virtuosity” and the ability to invent, Lila gets “an odor of wildness” and an “energy that dazed” men, “just like the swelling sound of beauty arriving” to Naples. Lenù gets pimples and glasses. Some sirocco wind is at all times at Lila’s back, making her wealthy; making her loved; making her offended, brave, righteous; almost a model, or perhaps an actress, except she is married so young; the hero, the innovator, the victim, the star.

My insistence on fairness nearly convinces me that, in losing, Lenù should be winning something else. In spite of everything, what she envies of Lila is precisely what Lila, in turn, provides her with: content. That’s why Lenù sticks around. When a girl resembles a movie star, her conditions of living take cinematic turns. Life occurs to her quickly, impossibly, just like the montage of romance, while the plainer girl plods along, a subject higher suited to a documentary. But Lila’s shimmering existence seeps into Lenù’s. The “day by day exercise” of noting the “convergences and divergences” between them, the “lines between moments and events” and people deus ex machinas which evade one and land on the opposite. Envy makes Lenù observant, a student of contrast. Which is to say a greater author—good thing, since all of us write ourselves. While everyone plays the major character of their very own lives, the plain girl is forced to be slightly more thoughtful. She’d be written by Woolf, not Hemingway.

Doesn’t being graceful just mean not having to think? Nothing is laborious, every thing is effortless, every morning Christmas morning since puberty left so many gifts. The awkward plain girl is driven, as a substitute, to self-obsession. To make a craft of her posture, her eating habits, her odor, her laugh, why they fail her, how you can improve them, the variations that make them superior and winsome in that favored another person. The symbol of being a plain girl is a heart trying hard. Erasing, scribbling. Romanticizing her contours. Narrativizing her lack.

That is the bone Ferrante throws the plain girls, only to toss it out. Lenù becomes the author, sure, but even what shines in her writing, we’re given to grasp, derives from Lila’s unpublished work, effortless, with a “force of seduction” Lenù can only contain, transmit, emulate, as if tracing the trail of a comet along with her stubby pencil. Whatever prompt for reflection or commentary Lenù extracts from Lila, Lila extracts from Lenù too. In other words, don’t kid yourself, even Lenù’s silver lining lies in Lila’s shadow.

Perhaps the plight of the plain girl is redeemed by its realism. Women age terribly. The homely woman gets there first. Everyone knows the genetically blessed woman stays higher insulated, to a point, from humiliation, male disdain, poverty. That Joan Didion thought the streetlights would turn green for her strikes one as reasonably unhinged, until one sees her photograph, and knows it with certainty. Beauty opens like a trapdoor, to second possibilities, the good thing about the doubt, a job you’re unqualified for, someone who will marry you, in case you so require. The associated fee could also be a life out of touch. The plain woman operates under fewer illusions, at all times slightly closer to the reality. In Wives and Daughters, Elizabeth Gaskell’s last, unfinished Victorian novel, provincial Molly finds herself the stepsister of worldly Cynthia, whose “beautiful, tall, swaying figure” brews predictable scandal after which sidesteps it, at Molly’s cost. For Cynthia wears “her armor of magic”—all of them do, letting her slip, eellike, out of the same old scrapes, if only to then get into others. The unlucky and nameless protagonist of Marguerite Duras’s The Lover, fifteen, compares herself to her classmate, Hélène Lagonelle. Hélène is a virgin, her body “essentially the most beautiful of all of the things given by God.” One feels, as one reads, the monsoon brewing. Hélène is “infinitely more marriageable,” but “doesn’t know” what the girl with no name does, of typical survival. In fact not. We’ve read what she looks like. Such knowledge could be well worth the price of plainness, if only it didn’t require knowing women like Hélène. “She makes you wish to kill her,” the girl confesses.

And what of that final possible solace: that beauty is attended by its own type of suffering. Objectification. Underestimation. Abuse. Too many men and their egos. Much more seductive an idea: Do beauty’s higher highs mean lower lows? Does whatever miracle that plucks a beauty from the group set her up, too, for catastrophe? Crowns her a princess simply to cut off her head? Take a look at Lila within the Neapolitan quartet; she might get special treatment, but she also gets beaten. She loses a toddler; her anguish is as sharp as her nice bones. Plain Lenù studies, applies herself to an uphill climb, a subdued figure against a headwind, yes, but she does find yourself, on the entire, higher off.

Yet whatever delusional peace this line of inquiry brings us, Ferrante snatches back. No suffering of Lila’s stops Lenù from being jealous of her. “What more do you would like?” Lenù asks Lila, bitterly. But what more does Lenù want of Lila? The reply is as easy and sophisticated, as shallow and treacherously deep, as: Lila’s face, Lila’s body. The Neapolitan quartet undercuts that old, soothing sentence, that compulsive effort to compensate, to equalize, one which my very own brother noted I used spitefully in highschool, every time he mentioned a reasonably girl: “Yes, she’s beautiful, but…” But nothing. We would discover with Lenù, but who reads Ferrante’s books and desires to be anyone but Lila? It’s not all good, it’s just every thing.

●

I fly from Marrakech to London. I wait in line on the airport as a young man is berating a young woman, who begins to cry. I board and discover that by some hellish windfall, the lady is sitting next to me. I’m looking good lately, perhaps because I’m finally well-loved, but that’s for one more story. The girl tells me every thing. She lists atrocities but saves, in a quiet voice, the worst for last. “He said I used to be average-looking.” I can hardly stand to fulfill her eyes. The boy is a couple of rows behind us, chatting up a reasonably stranger. “You’re not,” I say. “It doesn’t matter.” I touch her back. Something is going on between us, very wonderful and sad. Then in the course of her sobs she holds her hands up, and laughs slightly. “I’m sorry,” she says, after which crying harder, her voice breaking: “It’s just your hair. It looks so… beautiful. It seems so… soft.” It’s hurting her. I put it up.

In the primary of the Neapolitan novels, Ferrante places a wealthy, “superior” girl in green—green shoes, green jacket, green bowler hat—green, the colour of envy, in Lenù and Lila’s path. By the second book Lila stays apprehensive over her. “You’re much prettier than the girl in green,” Lenù consoles her, then thinks, “It’s not true, I’m lying.”

●

Some evenings i watch the truth TV show Love Is Blind, where the hierarchy of beauty I resent is toppled, then reasserted, to my masochistic schadenfreude. Singles date without laying eyes on one another, only meeting after becoming engaged. Nobody fares worse in this system than the unattractive woman paired with the better-looking man. Consider her fate as I do, on the couch, over ice cream. Alone, she meets her latest fiancé. He kisses, compliments, gropes her, perhaps sincerely. She’s gorgeous, he says. She isn’t. We eye him as suspiciously as she is beside herself with joy. Days later, at a pool party, the couples reconvene. He sees the opposite women for the primary time, and beside them, her, the one he selected, ultimately in context. His face falls. It’s precisely at this moment he ceases to like her.

Other evenings I turn on I Am Georgina, on Netflix. It infuriates me, her story, the entire premise, Georgina Rodríguez, the surprising partner of football superstar Cristiano Ronaldo. How, like thousands and thousands of other women, she once worked in a store, playing nice along with her customers, despising her days. How, unlike thousands and thousands of other women, there existed something in her face so naturally beautiful as to unnerve Ronaldo, to stop him in his tracks when shopping, to impel him to take an interest in her. To maneuver her into his mansions, where she might live in luxury, caring for his mysterious, surrogate-born children, accruing Instagram followers, purses, a reality show, the guiltless blessings of the born lucky. She goes to work by bus. She leaves by Bugatti, perpetually. It riles me up. I activate the tv and I watch her and watch her until I like her and hate her, as I’d a friend.

●

At the primary faint signs of aging, relentless K is swift to get work done. Botox. It rankles me. We’re 26 now; isn’t she drained? Energy is neither created nor destroyed, so I search my brow for her wrinkles and find them. I visit her dermatologist, taking the good distance, dragging my feet, vain enough to have booked the appointment but not so vain I might have gone unprompted. The doctor prescribes me: one syringe of filler, to boost me from one level to a different, as she did my friend. I infer: two syringes, to shut our gap, make us level. An old wish. I nod, close my eyes, grip the table. Beauty, incoming. She readies the needle, then the primary injection site. My eyes sting, I feel, on the scent of the alcohol pad. Then some misgiving in my face stops her. “You already know,” she says, slowly, “You and K usually are not the identical, you might be several types of… attractive, you don’t must rush this.” Implicitly: I’m not as pretty. I don’t have any such pressure, to prejuvenate, or invest. I sit up. The insult frees me. I could almost kiss her. I float to my automobile and drive home dancing, catching my flaws within the rearview mirror, like darlings an editor didn’t make me cut.

I’d gone to finally compete with K but settled for comparison, that poignant force that had at all times pushed me, turned my page, compelled me to try harder, thickened our plot by lending it subtext. I’m not the gorgeous friend; that’s not my category. Within the schema of how I understand myself, it’s simply not my place. The hierarchy of beauty parcels out different experiences of femininity. Mine mattered, and had grown on me, or perhaps I had grown around it.

And we reach some extent where we are able to speak about it. Not our own looks, which we at all times discussed, however the no-man’s-land that at all times sprawled between them. We thought it was contested, but really it was ours. I broach it fastidiously, at first, like it’ll bring her power over me. I broach it more boldly once I understand it brings power to us each. A way of freedom. K reads the draft of this essay. I act out the fake ID scene and we laugh. It’s different than after we were thirteen, on the beach, and I asked the kid we babysat who was prettier, after which I put my face within the water like a Victorian heroine and tried to drown myself, but not very hard. Something has modified. We’re getting older. The breathtaking great thing about a young girl eventually exhales, deflates, all of us start looking similar, in a decade or two we’ll fall into some binary of well-kept or not well-kept, after which what’ll matter is money, which fingers crossed I’ll have. But with beauty slowly, imperceptibly, leaving her, am I losing something also?

I could be no great beauty, but I’m no innocent, either: the one thing that feels higher than being chosen is being slighted. I knew what I used to be doing, with that boy, with my classmate, the kid we babysat, forcing each to play a test where the best answer, K, would at all times be flawed, would at all times shock me, gloriously, painfully, but never surprise me, confirming because it did what I already, irrevocably, knew. The rehearsed and yet devastated response it gives me license to perform. Admit it. There’s an influence to melodrama; it’s why they call it drama queen. I even have a shocking friend who applies lotion to her stunning body, religiously, every night, from her clavicle to her small Egyptian toes, and maybe that is my version of that. A confused self-caress, interspersed with slaps, which smarts, yes, but says: that is my body, I’m here, give me a story, send pathos in my direction, eye rolls allowed.

We play these scenes over and once more like dirges. When Nino picks Lila over Lenù within the second book of the Neapolitan quartet, the sky falls in our stomachs. Yet why does it feel so good? Who can explain our anticipation of that, our desire to see it exercised, exorcised? I’m trying. The night that Lenù learns that Lila and Nino have kissed, she uses “poems and novels as tranquilizers” to subdue her grief. She crafts a narrative, a “frame of unattainability” through which her bitterness becomes “utterable.” Isn’t that what, by reading, we’re doing? Isn’t that why I stay less pretty than K? For the sake of additional practice. Practice at making, as all of us must, a bearable poetry, a livable story, with characters and twists, of that which might otherwise kill us.

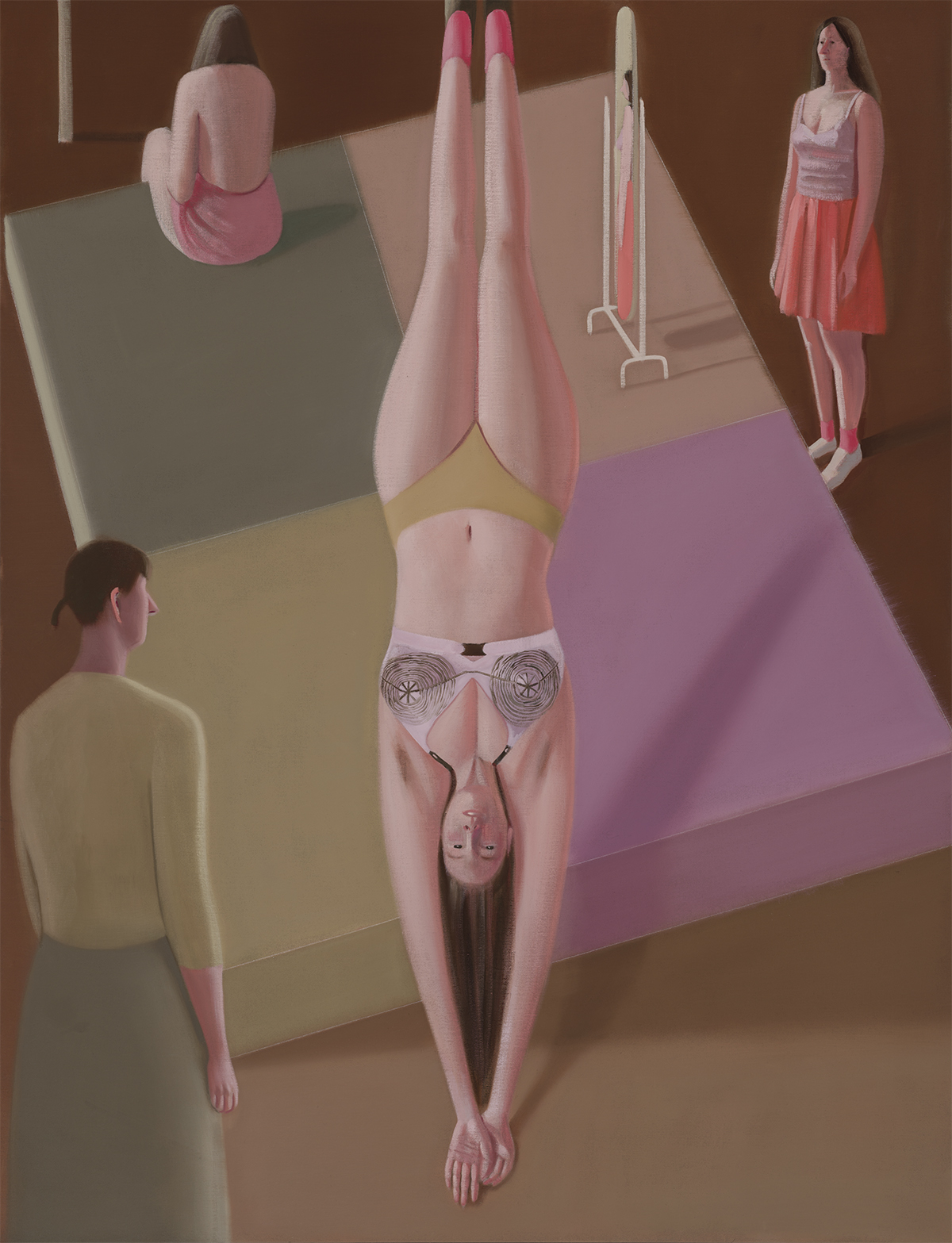

Art credit: (1) Prudence Flint, The Promise, oil on linen, 135 × 107 cm, 2021; (2) Second Hang, oil on linen, 142 × 109 cm, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and mother’s tankstation Dublin | London.

No Comments

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.