Getting braids—single plaits, cornrows or any style that weaves together three strands of hair—is a rite of passage for a lot of Black women in America. Who can remember spending hours as a toddler sitting on the ground between a loved one’s legs as your tresses were rigorously intertwined?

And today as adults lots of us frequent salons for more expertly crafted masterpieces. Nonetheless, unlike lots of our popular styles, equivalent to finger waves and rod sets, braids are greater than mere aesthetics. They bind us together. They’re an integral a part of Black culture—past, present and future.

ANCESTRAL ROOTS

The invention of ancient stone paintings depicting women with cornrows in North Africa shows that braids date back hundreds of years. Of their earliest known forms on the continent, the styles had a duality of purpose: Not only did they uphold societal customs, but they were also fashionable. “African women have a wealthy history when it comes to the ways they adorn their hair,” says Zinga A. Fraser, Ph.D., an assistant professor at Brooklyn College.

A particular look could indicate the clan you belonged to, your marital status or your age. For instance, a standard style symbolizing heritage for the Fula women of the Sahel region consisted of 5 long braids down the back with a small tuft of hair gathered at the highest of the crown. Hairstyles were passed down through the matriarchs of every generation—from grandmother to mother to daughter.

The Fula women also went to great lengths to present their hair beautifully. Silver and amber discs accessorized their shoulder-length braids. “These styles were like neat headpieces, worn down the center of the brow—regal-like,” says Tamara Albertini, owner of the braid studio Ancestral Strands in Brooklyn. The dichotomy between tradition and artistry existed in perfect harmony until the beginning of the transatlantic slave trade within the fifteenth century.

A NEW WORLD, A NEW MEANING

In accordance with Fraser, it’s inconceivable to know the history of braids, and Black American hair culture normally, without taking a look at the impact of slavery on African women. Along with the physical and psychological trauma it caused, an erasure occurred, she says. Before the captured boarded the slave ships, traffickers shaved the heads of the ladies in a brutal try and strip them of their humanity and culture.

Perhaps colonizers recognized the importance of the frilly strands. In any case, they sought to remove the ladies’s lifeline to their homeland. As the ladies endured the trials of slavery in America, braids became more functional.

“In a system [in which they] were just attempting to stay alive, there wasn’t time to make intricate styles,” says Lori L. Tharps, an associate professor at Temple -University and the coauthor of Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America. Sunday, which provided a slight reprieve from the torturous conditions, was the one day the ladies needed to prep their locks. “[So] braiding becomes a practical thing,” adds Fraser.

“[Hairstyles needed to] last a whole week.” Without time, resources or products, African-American women took to wearing their tresses in a more simplistic fashion. The ladies selected easier-to-manage styles, like single plaits, and used oils that they had readily available, equivalent to kerosene, to condition them.

Braids also served one other purpose: They became a secret messaging system for slaves to speak with each other underneath their masters’ noses. Tharps explains that “people would use braids as a map to freedom.” For example, the variety of plaits worn could indicate what number of roads people needed to walk or where to satisfy someone to flee bondage.

Despite the immense difficulties they faced during slavery, African-American women did their best to carry on to the ancestral tradition of wearing meticulously braided styles. Nonetheless, Emancipation in 1865 led to a longing to depart all things harking back to that horrific time behind.

As Black women flocked to cities like Chicago and Latest York throughout the Great Migration and took jobs as domestics (one in all the few positions available to them), braids soon became synonymous with backwardness. For some, plaits and cornrows were traded in for chemically straightened or pressed tresses.

“A braid was an indication of unsophistication, a downgrade of [a Black woman’s] image,” Tharps says. African-American women desired to look citified. With their newfound freedom, many selected to assimilate, and straight styles became the norm.

SAYING IT LOUD

It wasn’t until the Black Power -Movement of the 1960’s that our perception of our hair began to shift. The movement affirmed us and rejected the Eurocentric framework of beauty. Black Americans were developing a deep desire to honor our African roots, and our styles du jour reflected that.

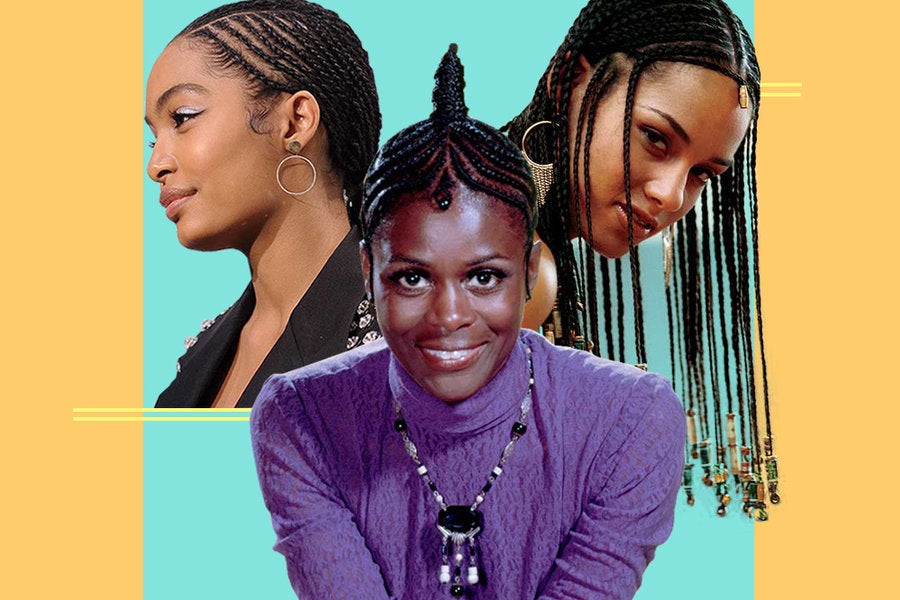

“Within the 1970’s braiding one’s hair on intricate levels was very much -connected to [the practices in] Senegal and Nigeria,” says Fraser. Within the 1972 Depression-era movie Sounder, a young Cicely Tyson sported cornrows and a scarf. Through the promotion of the Oscar-nominated film, she wore upward and crisscrossed gravity-defying braids that hovered round her crown.

The actress donned a similarly iconic look on a Jet magazine cover. Throughout the 1970’s and 1980’s, other stars like singer Patrice Rushen wore braids on the red carpet and through performances. Rushen often adorned hers with beads.

Over time braids became an outward expression of self-acceptance and self-love. And it was only a matter of time before others noticed. Sarcastically, Whites—the individuals who represent a culture that for hundreds of years has imposed its ideal of beauty on us—began to wear the types of our ancestors. Despite the undeniable fact that naturally straight hair shouldn’t be as adaptable for braids, the ladies were called beautiful and cutting-edge.

This was cultural appropriation at work. Yet while they were lauded, countless braid–wearing Black women like cashier Cheryl Tatum and telephone operator Sydney M. Boone faced negative responses: Within the 1980’s one was fired and the opposite forced to wear a wig because their hairstyles violated their company’s dress code.

Unbelievably, we’re still fighting the identical battle today. Just last 12 months Destiny Tompkins, a former Banana Republic worker, was told by her manager that her box braids were unprofessional.

MAINSTREAM MAGIC

Nevertheless, as hip-hop became the usual of popular culture cool within the 1990’s and early 2000’s, braids reigned with our female artists on the massive and small screens and in music videos. Janet Jackson made waist-length box braids famous within the 1993 flick Poetic Justice. Who can forget Brandy’s braids within the video for her smash debut single, “I Wanna Be Down”? She later wore them on her sitcom, Moesha, which ran from 1996 to 2001, and within the video for her 1998 primary crossover hit, “Have You Ever?”

Celebrity hairstylist Vernon François believes that braids reached latest heights during this era—punctuated by Alicia Keys’s stepping onto the scene: “When Alicia Keys got here out with her [look in the early 2000’s], it was a very big deal. She [further] commercialized the concept that you may be a successful artist with braids.” In 2016 Beyoncé paid homage to our heritage by wearing traditional double-row Fulani braids in her groundbreaking “Formation” video.

Regardless of recognition, braids are an inextricable a part of Black culture. We have now carried these styles with us throughout -history—from Africa to southern plantations to northern inner-city salons and beyond—even when our natural beauty was not acknowledged and with the plethora of haircut decisions available to us. From generation to generation, not only can we proudly opt to wear our braids, but we also reclaim them—time and time again—as our birthright and that of our ancestors.

Additional reporting by Rachel Williams and Hope Wright.

No Comments

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.