When your upbringing is a wealthy brew of Catholicism, Baptism, and evangelical summer camps, all played out against the patriarchal backdrop of Alabama, your intense attraction to other teen girls is best buried deep.

The Sunday Essay is made possible because of the support of Creative Recent Zealand.

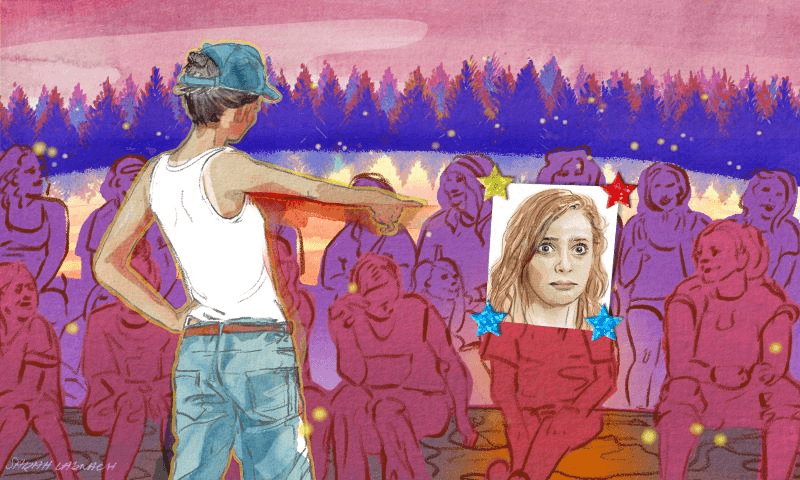

Illustrations by Sarah Larnach

When I used to be 12, at an all girls’ Christian summer camp in North Carolina, I got my first gay crush. She had silky black hair and almond eyes and a smile that split me open. The primary time I saw her, we were within the dining hall. There was something concerning the way she took up the entire pitch-sized hall – her skin electric, outweighing the scale and sound of chair legs screeching around tables of teenage girls buttering bread and spilling lemonade and singing worship songs. But there she was, a number of tables over from me, a syphon of orphic energy like one in all the archangels described within the book of Revelation, wings covered with 1000’s of fluttering eyes as a substitute of feathers. The considered her gaze falling on me was enough to trigger Armageddon.

In all those summers at camp, we only acknowledged one another once. She was in front of me waiting in line to leap on the water trampoline, her one-piece Speedo hiked up over ice pick hip bones, her nylon shorts rolled twice on the waistband showing light hair on the backs of her thighs.

Do you must get on with us? She asked.

No, y’all go ahead, I timidly replied.

She terrified me in probably the most rapturous way. I couldn’t go near her.

I knew the crush was a sin, but I didn’t dare admit it in prayer. Repenting would have made it real. As a substitute, I memorised Bible verses: Proverbs thirty-one thirty, charm is deceptive and sweetness is fleeting but a girl who loves the Lord shall be praised. She was within the cabin with the cool, pretty girls, so I convinced myself my infatuation along with her was merely jealousy of her beauty and recognition. Charm is deceptive, Mary. Don’t be deceived.

Then, on one earth-shattering evening, she played Danny Zuko within the camp’s rendition of Grease. I watched her from the audience with a slack jaw. Her hair was hidden in a backwards baseball cap, and, tucked into baggy jeans, a white singlet grazed her breasts like cling wrap over a tray of meringues. As she sang go grease lighting, finger pointing directly at me, I felt a rupture in my chest like a continent breaking in half. It’s because she is dressed like a boy, I told myself. That’s why I’m feeling this manner.

Nearly twenty years later, I finally got here out.

I was told outright homosexuality was evil, that it meant an everlasting sentence of teeth gnashing and skin scorching. But that never felt targeted at me – it all the time seemed geared towards men. Looking back, I ponder in the event that they even believed women may very well be gay. Sex was so wrapped up in penetration and power, they likely couldn’t conceive of it occurring and not using a cis-man. Two women having sex can be a knot unable to be untangled, a seeing eye to eye that will have confused the hell out of them.

Sermons geared towards girls focused on how we could best accommodate men – how you can warp ourselves, a stress ball squeezed so persistently it never returns to its original form. I used to be taught that man was created within the image of God, but women, we were a bone pried from Adam’s side. Barely even a counterpart, we were a fraction of lost flesh, the juice sucked dry from the marrow. Ephesians five twenty-two: wives, undergo your husbands for they’re the pinnacle of you. I used to be not my very own.

Once I was 13 I used to be given a purity ring, three tiny pinpricks on a paper-thin band. A dog collar would have made more sense. It symbolised my body belonging to men; first, to God, after which, my father. After all, when the time was right, my father’s ownership of me can be traded for my husband’s. Once I was twenty-one, I used to be told I had to come back out… as a debutante on the arm of my father, presented as an acceptable wife in a lamington pink ball gown. I had no grid for being a queer woman within the South because my survival hinged on men, on these scales they so delicately tipped of their favour.

My entire culture was, and is, still depending on the illusion of the binary. Without it, men haven’t any power. We southern cis white women have bought into the binary due to the privilege it allows us. We all know we’ll all the time be regulated by men, but so long as we keep conservatives in power we won’t lose our race privilege. We play together with the social hierarchy: dressing up as housewives, cooking dinner and spreading our legs when demanded, giving birth to heirs who proceed our racist legacy. So dedicated to this binary we’re, that Kay Ivey, Alabama’s second female governor, signed the country’s most anti-trans bills into law in April. SB184 and HB322 ban gender-affirming medical care, force teachers to “out” students to their caregivers, ban conversations about sexual orientation and gender identity with students, and ban students from using toilets according to their gender identity. The fast processing of those laws reflects the white-knuckled grip Southerners have on their power, which has nothing to do with the Bible; relatively, it’s a fearful response to the TikTok generation. After all white women aren’t leading the fight on this – BIPOC queers are, as all the time.

The delusion of white women is so deep in Alabama, I ponder if we now have some kind of collective Stockholm syndrome, if we actually prefer it this manner. Until my mid-twenties, I happily allowed men to make decisions about my body. Once I was 18, I used to be drugged and raped by a friend from church at a celebration in front of a crowd. Afterwards, I used to be kicked out of my Bible study and chastised by church friends because I “lost my virginity”. It was my fault – I had worn a low-cut dress! I had a crush on him before it even happened! I wanted it! At a fraternity party months later, someone sprayed graffiti on the basement wall: “Mary Mosteller and the bloody elephant massacre”. That’s what they called it – a lot blood on the sheets and floor they said it looked just like the slaughter of an elephant. The young man who did it apologised to my father, I forgave him, after which we dated for a yr. I believed our relationship was God working good from our sin. Losing myself to men was so ingrained in me, I ponder now if I actually cared for the boys I dated, married, slept with; or if it was just a few submissive and reverential root that calcified in me. How could I give up to my feelings for girls, when it meant abandoning my obligation to men?

The first person I told about my attraction to women was my sister. I used to be 23. We were walking along the beach in Charleston, South Carolina, murky ocean lapping at our feet, palm trees immobile within the thick air as if the humidity encased them in resin. Sadly, it wasn’t a lot a coming out because it was a repentant confession: I’m drawn to women and I comprehend it’s a sin.

I shovelled my toes into sand, uncertain and awkward.

I don’t know why I’m feeling this manner. I feel it’s due to society’s oversexualisation of ladies, I said.

What do you mean? She asked.

You recognize, like, the media portrays women in ads and music videos with barely any clothes. It’s objectifying. I feel I even have been manipulated by that, like seeing models and celebrities has made me start objectifying women too. Made me start, like, being drawn to them.

Seagulls crossed the blurred horizon, the water unsure when it became sky.

That is sensible, she agreed, quiet, kind, listening. I hardly remember her response, only a vertiginous daze. My solution was to stop watching a lot TV – and definitely stop watching lesbian porn in secret.

That yr, 2014, some invisible tentacle ripped me out of Alabama. The pressure of the South was an excessive amount of; like canned fruit, I had fermented slightly. I landed in Aotearoa in a tornado of culture shock. I struggled to grasp the way in which Kiwis hold their vowels so near their chests. Grandiose American outbursts were replaced by mumbling mocking and self-deprecating jokes. And each time someone asked where I used to be from, they began singing my least favourite song: Sweeeeet Hoome Alabama.

Yet, I made friends. The vagina-owners I met here didn’t make sense to me. They dyed their hair orange, didn’t wear bras, didn’t shave their legs or armpits; they were career-driven lawyers, doctors, engineers; they made decisions, and folks followed their lead. They didn’t hearken to men the identical way I used to be used to, didn’t feel the necessity to respect their wishes or admire them unless earned. It was astounding.

My friends in Alabama were having their first babies at 23 and getting Botox at 29. They’d reformer Pilates memberships and went on crash diets while their men drank themselves bloated beer bellies and stayed on the office until 9pm as a substitute of helping look after their children. They called themselves bad wives for being too drained to cook, for eating an excessive amount of, for not being within the mood to have sex. Meanwhile, in Aotearoa, my friends and I’d exit dancing on a Thursday, cuddle, drunk until 3am four-deep in a queen-sized bed stained by the grease of empty pizza boxes; then go to work, get promotions, rule the world. I’ve never felt so loved.

Aotearoa is removed from perfect, but comparatively, it feels hopeful. To see women in office, conversion therapy banned, gun laws tightened, and the beginnings of decolonising education has re-instilled a few of my faith in humanity. In Alabama, I used to be not taught anything concerning the Choctaw tribes whose land I used to be occupying, the land my ancestors stole. During my teaching degree, I took a paper on Te Ao Māori and Social Justice within the Education System. This learning is my most catalysing experience thus far. Every construct in my world crumbled, and suddenly all I could see was injustice. This learning cemented in me what had all the time felt fallacious: my version of Christianity was rooted in white supremacist patriarchy. This was the nail within the coffin of my evangelical identity.

Change didn’t come quickly though. Coming out felt like a soft launch that took several years, and for a while, I felt like I used to be living a double life. There have been gloriously free days – woozy from purple Pal’s at Big Gay Out, pink glitter stuck in my hair even after two washes; and dazed after a soft kiss in my bedroom with my flatmates cheering on the opposite side of the door. And there have been days I felt fake – unsure whether a Barbie-pink sock-hop skirt was gay enough; or told by a crush that she thought I used to be bad at telling men no. Even with all of the acceptance here, I used to be afraid of being ostracised from this community I had all the time been a component of but barely interacted with. This was made tougher by backlash in Alabama. Acquaintances spread rumours around my hometown that I left my ex-partner for a lady; cousins called fearful that it was actually a mental illness causing me to have manic episodes. Coming out here was difficult enough, so I distanced myself from home, blocking anyone that may slide into my DMs in an try to force me to repent for my backsliding ways. This was made easier by the closure of Aotearoa’s borders, and I didn’t go home for a number of years.

Sometimes I feel guilty for not having to take care of the backlash in person. I feel imposter syndrome that I missed a fundamental a part of being queer, that I didn’t have the craze so many young queers experience when raised in unaccepting religious homes. And yet I’m experiencing that rage now as I come out to my family and friends. There was rejection, except I even have the privilege of getting more tools in my kete and three years of therapy guiding me through it. This time of separation helped me forge my identity. In leaving home, I got here home to myself.

This July, I went back to Alabama for my grandmother’s funeral. While reading through my childhood journals, I discovered one from the yr I had my camp crush. I scoured the pages for her name. She wasn’t mentioned. As a substitute I discovered lines talking concerning the boys who worked within the kitchen or the male tennis instructors who were twice my age. My only allusion to queerness was this one line: The kitchen boys were there last night and so they are sooo hot! I’m at an all-girl’s camp; they’re my only option. At first, I used to be disillusioned. Why hadn’t I written about her? Then, I noticed pages ripped out, twink smeared over paragraphs, and I remembered an old feeling: fear. After all I didn’t write about her – I used to be petrified of someone checking out concerning the feelings I justified to myself as misplaced. This line was overcompensation, a performance to attempt to persuade myself I used to be straight.

While you come out later in life, people have a whole lot of questions. When did ? Why didn’t you come out earlier? Why have you ever been lying this whole time? These questions got here from family and friends, however the worst person to listen to them from was myself. After years of convincing myself I wasn’t gay, I even have now needed to persuade myself that I’m, and that there is no such thing as a certain way that it’s speculated to look.

Taking my time to get here could come right down to demeanour – a few of us fight, a few of us freeze. Submission was easier for my nervous system. We hear a whole lot of stories from individuals who fight against, but there are those of us who lie quietly within the background, wondering if we’ll ever be brave enough. Ultimately, the explanation it took me so long doesn’t infringe upon my queer identity. I mustn’t need to justify my story to anyone, not even myself.

While I used to be home in July, I got here out to my oldest friend. We have now known one another since we were two – we’ve bathed together in bathtubs and baptism pools, witnessed one another’s first crushes and first communion. She has stayed within the South, largely adhering to the cultural norms we were raised in. Yet within the ebbs and flows of our friendship, irrespective of how much I even have withdrawn, she has still pursued me. That evening, we sat at an outside restaurant, our chilled wine glasses perspiring on thin napkins. She probably already knows, I assumed, it’s obvious from social media and the writing I even have published. I fiddled with my glass, making doodles within the condensation with my fingertip and fingering the stem between sips.

I would like to inform you something, I said nervously. You might have already seen it, the story I got here out with?

Which one? She asked.

The one concerning the first girl I dated.

Cool, she said. Where can I read it?

On my Instagram, I said. I’m bi, by the way in which.

I figured, she laughed. Thanks for telling me. Were you nervous? To inform me?

No, I lied.

I’m glad, she said. I like you.

I like you, full stop. Not I like you although you’re gay, not even I still love you.

She continued asking if I had gone on any good dates recently – normal questions. As I spoke, I watched her brown eyes on me. Her pupils looked open, like stiff windows with creaky hinges thrust wide, letting in a sea salt breeze and kicking up dust.

No Comments

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.